The Ebo forest, with an area of 2000 km², proposed to be erected as a protected area by the State of Cameroon in collaboration with WWF in 1985 has not been classified despite petitions and letters of encouragement from communities’ residents, elites and defenders of the environment. This forest is teeming with a population of endangered great apes, elephants and other small animals. There is also the arrival of agro-industries such as Azur (Green Field), CREFAT, palm oil producing companies with plantations of more than 123,000 hectares on a site where the carbon sequestration rate is estimated there. to more than 35 million tons. This forest landscape, which until then had no legal status, is now suffering from ever-increasing deforestation and poaching, a source of the rise in illegal logging. Faced with this, the local populations have no way out for their development. While the latter were finally waiting for this forest landscape to be erected in a legal framework more conducive to their local aspirations, it was then that the Government decided to segment it into 02 UFAs in June 2020. Part of this UFA was classified in August 2020 by decree and was already planned for operation on the site planned for the park.

Faced with this situation, a lot of ink has flowed both among the local populations and on the side of civil society, politicians and even international opinion in order to put pressure on the State to change the classification decision. For the state, he believes that the UFA will help achieve national development goals. And for the opposing camp, the UFAs that have always existed in the northern part of the landscape have only served operators without any visible contribution to the communities. Since the same causes can produce the same effects, they think they have a say in the management of resources in their territory. This made it possible to engage in numerous dialogue sessions with the State, having at the center the Banen, local populations who were removed from the landscape so that the site could be set up as a Conservation Park. Their indignation which was supported beyond the national territory had brought the State to order and the project of creation of UFA was abandoned. A victory that will allow an in-depth analysis of the uses of the local populations so that in any future process.

Thus, in the face of all these debates, the Banen men were at the front to claim their right to their cultural and ancestral heritage. The rights of women have not been explicitly elucidated, yet they are the first direct victim of the uncoordinated actions of the State on their ancestral lands. They were not heard in the debates that were organized around the status of the forest, yet they are at the heart of food security in the Ebo landscape. In order for the voice of women in the Ebo landscape to be heard in this debate, for a contribution to the sustainable management of resources, AJESH with the support of GGF wanted to pave the way for understanding the place of the uses made by women for development of a future sustainable management plan for the forest.

The voice of women in the sustainable management of the Ebo forest landscape

Uses of women in the Ebo landscape

Women, on whom nearly 75% of the family burden rests in the villages of the Ebo landscape, practice 90% of agriculture. Among other things, it is also the collection of NWFPs, group fishing and small trade. Recently, with logging, PNFLs (wild mango, moabi, black pepper, djancent, hazelnut, leaf for packaging, etc.) are disappearing exponentially. They are more and more distant from the center of the villages. These precious cessâmes formerly collected behind the huts today require more energy expenditure for women because they sometimes have to go more than 10km from the village.

For agriculture, it is their main activity. They are not accompanied despite the problems related to land allocations which they encounter. The desire of the State to classify the lands on which they derive their source of subsistence, without a support plan, is a brake on their development. And the women of the landscape protest against the actions of the State against their use, a source of family fulfilment.

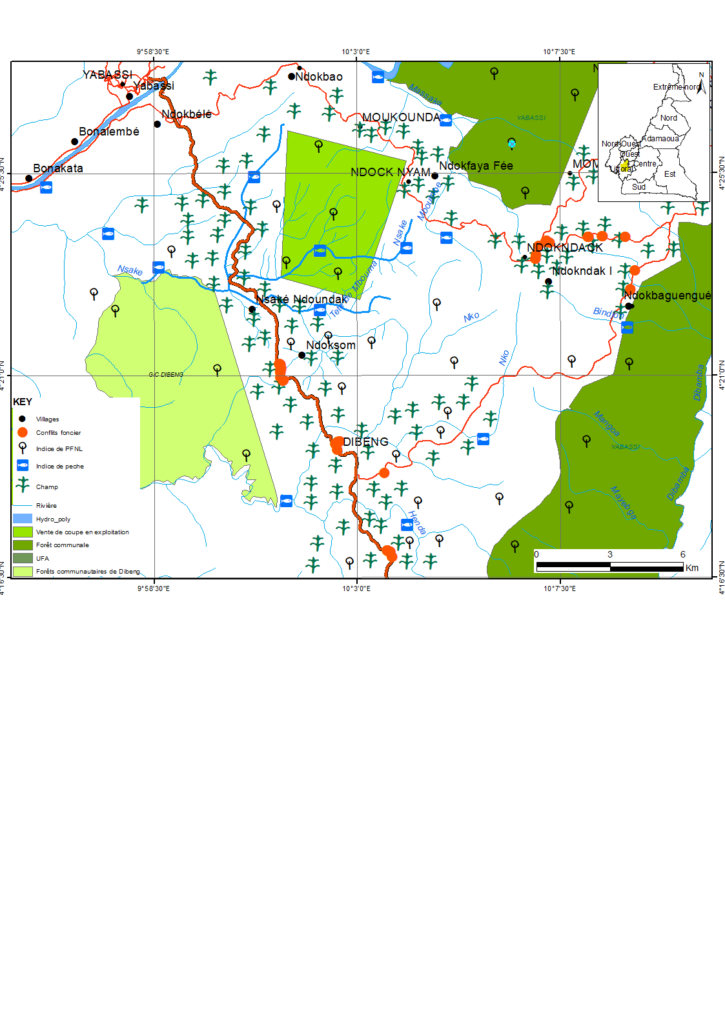

Thus, AJESH organized in-depth discussions with women in the landscape and resulted in the development of participatory maps on the uses of women in the villages of Nsake, Dooundack and Dibeng. These maps, drawn up for each village and merged into one, show the spatial distribution of women’s uses as well as some of the conflicts encountered. But these conflicts do not emanate from state land allocations but from the shrinking of women’s areas of activity with the growth of forest allocations to forestry companies and land to agro-industries. This map shows, in fact, the current mode of resource management by women in the Ebo landscape despite this small sample, there is a need to involve all women in the landscape.

Figure 1 : Forest usage by women in Dibeng-Nsake © October AJESH, 2020.

In the mapped villages, the source of water supply by the household is from the surrounding rivers. Most of the latter are polluted due to illegal logging, thus increasing the level of vulnerability to diseases among those who have neither a health center for the minimum service nor a road for the evacuation of agricultural products. Even polluted waters do not allow the survival of the poisons that women collect during known seasons. NTFPs are quite far from villages and suffer the effects of logging. Agricultural activities are reduced around the villages.

Concerns about the shrinking spaces in which women use is made to be addressed in the decisions of classification of forest areas on the Ebo landscape. The result of the latter is the shrinking of agricultural areas. The concentration of agricultural activities along communication routes for agricultural activities generates many disputes to which women are more vulnerable. In the villages of Nsake, Dibeng, Ndokbelle, Ndockbao Ndonbaguengue, Nyamtan, Londeng, Ndokama, Moukounda and Ndoksoum, more than 500 land disputes concerning women have been counted. Nearly 80% of these women have never been able to bring their problems to the traditional authorities because they are “allogens” deported from the Ebo forest. They have a right to use the limited space. They lack the means of support in the exploited areas.

This proliferation of conflicts, on analysis, is the result of years of biodiversity management centred on the State and private investors without taking into account the uses of women in the landscape. The latter have restricted the power of access to land as well as the collection of resources that are a source of subsistence for families. This restriction having narrowed “accessible space” creates many conflicts that are disadvantageous for rural women in the Ebo landscape. We must indeed think of a solution for classifying forest areas that would take into consideration the uses of women.

Impact of forest allocation decisions on the uses of women

In this wake marked by non-integration, women in the villages of the Ebo forest landscape find it difficult to freely exercise their activities for the survival of families. Their non-participation in decisions for the management of resources on their land limits the extension of agricultural activities and the exploitation of NWFPs. These uses of women and many others are plagued by non-inclusive land use decisions. This is not without effect on the socio-economic development of the villages. Analysis on the contribution of logging to local development between 1980 and 2020 having shown a negative balance, it is time to think about a form of participatory management of resources in the Ebo forest landscape.

If, moreover, it is known that participatory land management with women can contribute to their empowerment and considerably reduce community poverty, it also results in an increase in agricultural production and access to various credits.

Faced with this situation, food security in the landscape will depend on the involvement of women in the governance of existing resources. This involvement requires taking into account the uses of women in activities related to resource management. Discussions held between chiefs and women leaders have already eased access to customary land ownership for women.

Perception of women on resource management in the Ebo Landscape

With the race of actors towards the exploitation of resources in the Ebo Forest Landscape, it is necessary to see with women, more than 40% of the agricultural workforce, the orientations of the management plan for these resources. .

On the one hand, some believe that the creation of the UFA would be a godsend for the communities because it will bring roads, infrastructure and development. But they went one step further by evaluating the contribution of past logging to the development of their land. This assessment shows scruffy communities, deprived of the resources (raw material) for their subsistence without any social infrastructure. They are even rather threatened with limited access to their ancestral lands. For this, the creation of UFAs in this ecosystem could benefit the women of the Ebo landscape.

On the other hand, women believe that the creation of a forest reserve/community forest under community management will benefit them. This can reduce current pressure on land, increase tenure security and promote sustainable resource management.

Thus, the position of women for an integrated management of the Ebo forest landscape is known and concerns the actors and the form of decision-making. This position is a form of decentralization of resource management with the objective of accelerating local development with full participation of local populations.

Figure: Concertation meeting with the chief and women lead

© AJESH, October 2020

The women of the Ebo forest landscape feel excluded from the management of resources on their land. With the arrival of agro-industries, logging and conservation, they are not found in any of the projects. This situation creates a gap between the communications made around the projects and the needs of women in order to meet family needs. This is why they think that the creation of forest reserves for their village where they will be able to contribute to the integral management of resources would be beneficial for local development. Projects dictated from above and imposed on their territory have until now only further impoverished resources and families. Projects that do not emanate from the communities and where they have no contribution are the source of the ambient poverty that prevails in the Ebo forest landscape.

The women of the Ebo forest landscape are very likely to participate in nothing if the State and private investors do not change the operational system in the management of current resources by giving them autonomy over the management of resources on their land. The destruction of the cultural barrier for women’s access to land ownership must be accompanied by the safeguards and sustainability of the traditional values that biodiversity brings to the entire population. For a participatory and harmonious community development with the uses made by women, it is necessary to consolidate cultural practices to a very widespread lack of integration in the resource policy of resources.

Thus, the future of the Ebo forest and its entire landscape must be made with women. There is a need to reconcile future decisions on this forest area after numerous pleas that led to the failure of its classification as a production forest. There would be a way of a framework for consultation on the management of space with community visions oriented towards empowerment of local management with a contribution to safeguarding the uses of women. The participation of women and local organizations in the development and implementation of the resource management plan must be a necessity. This participation, as desired by the latter, is a plea for the inclusion of their subsistence activities in the resource management plans on their land. For her there is a need to continue to benefit from environmental services as well as their economic value. The denaturalization of their environment, their remoteness from their living environment and the loss of cultural values are obstacles to local emergence.